Vlad Lavrov on how to work around opaque systems that prevent the access of public information.

“Even in the most untransparent countries, the government still publishes a trove of documents which would often contain important information. Also, if you can’t find the information in one country, think about other jurisdictions that might have it, as very few important business deals in the current world are 100 percent local.”

What were the major findings of your story?

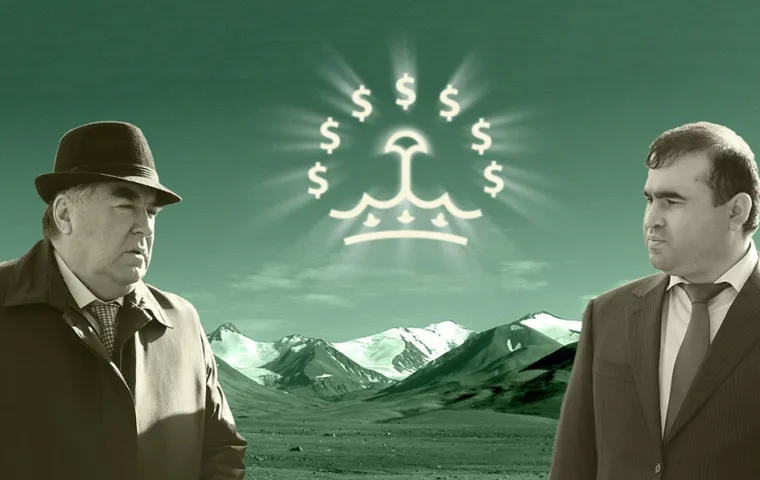

We documented the main business activities of Faroz, a company owned by the Tajik president’s son-in-law, and showed how the market was artificially skewed in its favor by the president’s decrees.

What impact did your story have?

The company announced discontinuing its operations due to “unfair media coverage.” This story proved that open source investigative reporting is possible even in the toughest of places.

Did you receive any funding to do this story?

No.

How did the story start and how did your team decide on the first steps to take in working on this story?

It started at the IR training in Tajikistan where we helped local reporters get company records from the local registry using a brief window of opportunity when the government would allow this. Some of the records back then helped start documenting the president’s family holdings.

How long did it take to report, write and edit this story?

We obtained our first records in 2013, started reporting actively in 2016 and the story was published in 2018.

What challenges did your team face while working with sources?

We totally anonymized the Tajik reporters who worked on the story. Also, we only worked with sources who lived outside of Tajikistan, as we wouldn’t be able to guarantee their safety otherwise. We kept all the communications encrypted, naturally.

What resources and tools did your team find useful? How did you organize your data and documents?

We found a way to scrape the Tajik company registry, which otherwise was not available, and that really enabled us to map out the entire structure of Faroz that no one was able to do prior to that. Because this information was not accessed by anyone before us, the real beneficial owners didn’t feel the need to hide their ownership.

What other challenges or barriers did your team face while working on the story or series, and how did you overcome these challenges?

The absence of land and court records in Tajikistan was the main challenge. I think to some extent you really cannot compensate for this. But we’ve been able to use the footprint that our main characters and businesses left abroad to the maximum potential.

What advice would you give journalists working on similar investigations?

Even in the most untransparent countries, the government still publishes documents that often contain important information. Also, if you can’t find the information in one country, think about other jurisdictions that might have it, as very few important business deals in the current world are 100 percent local.

Did your team face any pushback during or after the publication of this story? If so, how did you address this?

One of the sources was kidnapped while abroad and forcibly taken back to Tajikistan where they were forced to denounce any criticism of the regime. Thankfully, there was a swift international reaction and they were released quickly.

Did working on this story change your perspective as a journalist?

I never realised that some stories can take so much time, mainly because of excruciatingly painstaking data collection.