Listen now

Episode transcript

NEWSREADER

Police in Paris have removed hundreds of homeless migrants from a squat in the city, which is believed to be the biggest in France.

MICHAEL

He tell me if you don’t have a job I do not give you the house here.

FARIS AL KALI YOUSSOUF [translated from French]

The only solution is to go around Paris and help them in tents. And that, I can’t continue doing because it hurts my heart.

JULES BOYKOFF

You might call the Olympics an exercise in trickle up economics, the money tends to flow up toward people who already are doing quite well, economically. And so you see that in city after city after city, it’s not a Paris thing. It’s not a Rio thing. It’s an Olympic thing.

AMÉLIE OUDÉA-CASTÉRA

What I want to emphasize is that it has nothing to deal with the Olympics. These policies, they were implemented before the games, they will be implemented after the games.

I am the Minister for Sports and the Olympic Games and it has nothing to see with the Olympics.

HOST (ANDIE CROSSAN)

Welcome to State of Play. The podcast where we investigate the ways that hosting big sporting events change big cities.

This season we’re looking at the Olympic games—past, present and future.

I’m Andie Crossan.

So we are just days away from the lighting of the Olympic cauldron in Paris.

NEWSREADER

Paris hasn’t played Olympics host for 100 years so organizers are leaning into the city’s history.

HOST

What a summer for France.

Welcoming the world for the Olympics and Paralympics.

NEWSREADER 1

President Macron just this week announced 400 more soldiers to protect the games…

NEWSREADER 2

…Bridges, major landmarks, it seems like every inch of Paris is undergoing a major facelift for the event.

HOST

And President Macron deciding to call a snap election.

NEWSREADER

It is the left alliance that is the biggest party. And yet we are now, with the Olympics coming up, in a situation of deadlock.

HOST

All that and crowds of people swimming in the Seine for the first time in a hundred years!

Well maybe not that last thing.

NEWSREADER

Paris has spent more than a billion dollars in recent years cleaning up the river. But according to a company testing the water daily since April, not a single test has shown water quality suitable for bathing.

HOST

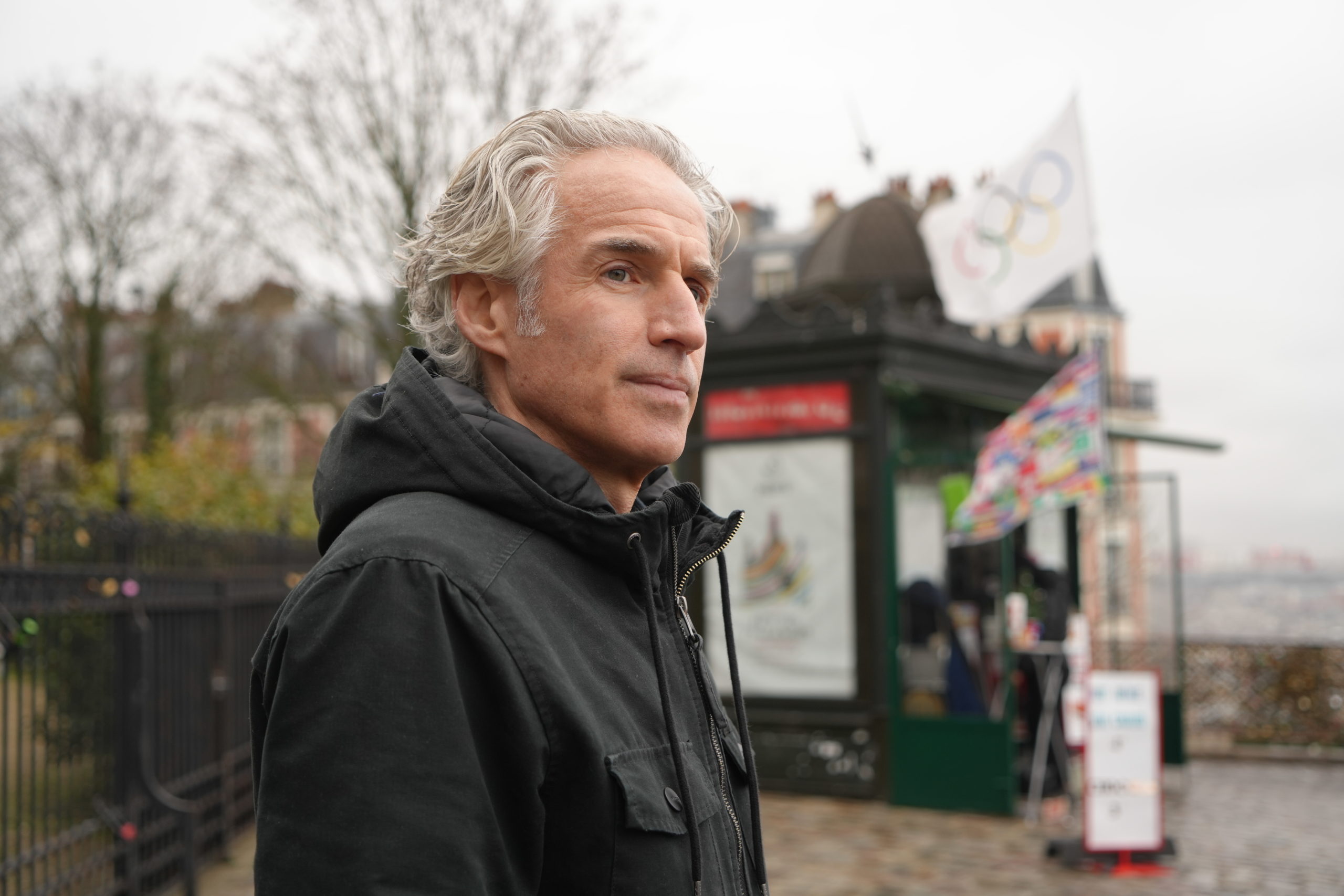

For this episode of State of Play, we’re gonna stay in Paris. Where a few months ago, I spent an afternoon with someone who knows all about how the Olympic Games can change a city.

Jules Boykoff has written six books about activism and political movements around the Olympics.

He’s a professor of politics and government at Pacific University in Oregon.

Honestly, Jules is a unicorn.

He’s not just someone who studies and writes about this stuff.

He’s also a former athlete.

Jules played amateur and professional soccer, including on the under-23 U.S. men’s team.

He understands the passion for sports and also the impacts of hosting big sporting events.

Jules kindly agreed to spend an afternoon with me in Paris strolling through the streets.

And we get real about what’s happening at this summer’s Olympic games.

But first… it’s Paris so…

ANDIE CROSSAN

So where do you think we should grab a coffee?

JULES

Well, there is a place right there on the corner.

ANDIE

Sure.

JULES

Although, you know what, I had one there the other day and it—

ANDIE

It wasn’t—

JULES

Not sure.

ANDIE

It didn’t rock your world?

JULES

…did not rock my world. So maybe wanna try a place over here maybe?

ANDIE

Yeah let’s go for it.

JULES

Okay.

ANDIE

And maybe we can sit outside.

HOST

So with a nice cafe au lait in front of us and Parisiens hustling past us to do their Saturday shopping, we settle in to talk about sports—and how sports came into Jules Boykoff’s life as a kid growing up in Madison Wisconsin.

JULES

We would go to University of Wisconsin, Badger sports games. My dad would take us to basketball, football, soccer, volleyball.

My dad was a really big women’s basketball fan, women’s volleyball fan. So we grew up on a steady diet of Bucky Badger.

ANDIE

[laughs]

JULES

And my mom was a really avid swimmer. My mom’s physically disabled, so she was, she had polio when she was a kid. And the doctor told her she was never gonna walk again.

And she tried some experimental ways of overcoming polio, and miraculously at work she walks with a severe limp. So that made running for her impossible, but she’s a, she’s a big swimmer.

Even to this day she’s a really big swimmer, and so she was an athletic inspiration for me in many ways.

My dad wasn’t sporty. If I, if I could get him in the yard to play catch with the baseball, that was about as far as it would go.

ANDIE

[laughs]

So we would watch a lot of sports and we supported Wisconsin athletics.

Played a lot of hockey growing up ’cause it was Wisconsin, you just go down to the local rink and play until your toes were too cold.

So yeah, I mean, it was sort of a part of the family in a way, but certainly not competitive. It was always just, hey, let’s get out there and try to be healthy and support our local team.

HOST

At this point, suitably caffeinated, we start our walking tour of Paris. And Jules tells me about his first time playing soccer when he was a kid.

JULES

My mom, when she was in a lot of pain and I was, I guess a pretty active little guy, she enrolled me in soccer when I was four years old and on an under-eight team. So all the kids were really big and the coach said, “No, you gotta be older to participate.” And she basically just convinced them otherwise.

HOST

So there was little four year old Jules running up and down the pitch with kids much older than he was.

He grew to love the game—and spent years playing on recreational teams before getting serious about soccer.

By 19 he was selected for the U.S. men’s national team.

That’s when he left the U.S. for the first time in his life to travel to France to compete. The year was 1990.

JULES

It kind of blew my mind, honestly this, this kid from Wisconsin who didn’t expect to be there.

And then I, I guess I always told myself though, too, when I was there, tried to convince myself that I was supposed to be there. I wasn’t always successful at convincing myself that I was supposed to be there.

But you kind of have to do that. Tell yourself you belong, talk yourself into it.

ANDIE

At what point did your shift in thinking or, or evolution in thinking come around the role of sport and your connectivity to it?

JULES

Well, it’s embarrassing in some ways that I didn’t figure it out earlier. I should have.

One thing that opened my eyes a little bit when we were playing in the tournament in France was that I fully expected, having grown up on a steady diet of pro-U.S. propaganda, that we were going to be well received everywhere we went.

Like they’d be cheering for us to beat Brazil, to beat Yugoslavia, to beat Czechoslovakia, certainly to beat the Soviet Union.

But that just wasn’t the case. We got kind of a cold shoulder reception in a lot of the places that we went.

HOST

Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Soviet Union—remember—this was 1990 and all of these countries still existed.

But that cold shoulder extended beyond Jules Boykoff’s experience in France.

JULES

Playing for the under 23 team, some exhibition matches in California. It was a friendly match between a German team and a Mexican team.

And we were all sitting there in our shiny blue sweatsuits. And they announced that we were there.

This game was being announced in Spanish, by the way. And so they announced that we were there. And I remember distinctly, ’cause I mean, I speak Spanish, so I understood what they were saying.

And they’re like, we would like to welcome the under 23 men’s national soccer team from the United States. And then it was like, golf clap.

ANDIE

[laughs]

JULES

And I heard booing too, so.

ANDIE

Oh no! [laughs]

JULES

And that was in the U.S., you know what I mean, so.

ANDIE

Not booing! Oh no.

JULES

Yeah, so in a weird way, actually getting booed in your own country opened my eyes to something. So it was kind of a slow—I might have been a slow learner at that time if I think about it.

But at age 19, 20, I was starting to figure things out that the U.S. wasn’t all that I was told it was growing up when I was going to public school in Madison, Wisconsin.

So in a way, soccer kind of helped open my eyes to more political realities.

HOST

That awakening led Jules to study political science at the University of Portland. And from there he headed north.

JULES

If you really want to know when it was, it was about 2009, Vancouver Olympics, just ahead of those Olympics.

I happened to know a lot of politically active avant garde poets and writers who told me I needed to get up there, because there was a whole lot happening around the Olympic games at that time.

At that time, I was writing about the suppression of political descent. That was my research topic academically.

And they said, “Oh, you gotta get up here because all of our dissent is being suppressed up here. And this will be an interesting case study for you, so why don’t you get a train ticket? Come on up.”

So I did, I set it up ahead of time. I was gonna write an essay about it for an online publication. Got up there, followed these activists around, listened to their arguments.

And that really opened my eyes to the Olympics. I sure wasn’t totally certain at that point that it, it was a thing that happened in every Olympic city. I just knew it was happening in Vancouver.

HOST

Now, 14 years later, having authored six books on the Olympics, he’s an expert on the Olympic machine—he spent time living near London ahead of the 2012 Games and he lived in Rio de Janeiro as the city prepared for the 2016 Summer Olympics.

So by now, Jules knows the playbook.

JULES

Whether it’s gentrification of urban space, whether it’s misallocation and misuse of public money, whether it’s the intensification of policing, whether it’s the propensity to engage in greenwashing, whether it’s the propensity to engage in anti-democratic practise, or whether it’s just like straight up corruption.

All those things already exist in society, and they get turbocharged by hosting the Olympic Games.

HOST

Paris is already getting that Olympic buzz.

There are Olympic logos on posters and shop windows as it prepares to play host to the games.

And like previous Olympics, Paris has a mascot and there are images of it all over the city.

It is supposed to represent a red revolutionary symbol, called a phrygian cap.

It’s triangular in shape and has googly eyes.

If you’ve seen it, you know that it looks like… well… a certain emoji.

I’ve brought you here to somewhere very special. And a highlight of our walking tour of Paris. I’ve brought you to the Olympic souvenir shop.

JULES

Oh yeah. All right. Let’s check it out. We can buy ourselves a red poop emoji. Is that what you said?

ANDIE

Yeah. I think that we can get … oh my goodness. There it is. Wow.

JULES

Oh my gosh, look at the size of that poop emoji. I mean…

ANDIE

There’s like a, I—okay, so I have to try and describe this. A poop emoji… with googly eyes with a Paris 2024 and Olympic rings kind of in its belly area. This one seems to have feet attached to the bottom of it.

JULES

The one on the top shelf, how much do you think that costs?

ANDIE

Okay. I’m not sure I’d pay anything for it, but I’m gonna say, uh, oh, it’s a tough one. I’m gonna say 15 euros.

JULES

15? Oh, man.

ANDIE

Are you gonna go in and check?

JULES

Oh, I will. Let’s do it. I’m gonna go three times that.

ANDIE

What?

JULES

Oh yeah…

…Wow.

ANDIE

What was it?

JULES

35.

ANDIE

35 euros. So it’s like 40 something U.S. dollars.

JULES

Yeah I’d say that that, uh, phrygian cap is about what, maybe 12 inches tall?

ANDIE

Yeah it’s like 10 to 12 inches tall. And it’s literally just a triangular-shaped red blob… for 35 euros.

HOST

With a sea of overpriced souvenirs behind us, we make our way towards the Seine, where the Olympic opening ceremony will be taking place.

JULES

Well, I think on the issue of gentrification, housing, and houselessness, you can see patterns when it comes to the Olympics.

1996 in Atlanta. Unhoused people were given one-way bus tickets out of town because they didn’t want everybody to see that there was unhoused people when they came for the Olympic Games.

I’ve seen this so many times now through history where there’s going—big promises around what’s going to happen. But in the end, it seems like people who are organising the Olympics and, and, and local politicians just want to get the poor people, get the marginalised people outta the way.

And how much you can blame that on the Olympics themselves? Uh, I think you can blame a fair share of it in the sense that if the Olympics weren’t here, we wouldn’t see the evictions of all these squatters according to the people who work on this on the daily here in Paris.

And it’s not just Paris, it’s all sorts of other places. When I lived in Rio de Janeiro, I worked with communities that were under intense pressure to move. They were being displaced.

One of ’em got a lot of global media attention, a place called Vila Autódromo. Overall 77,000 people that lived mostly in favelas—these informal communities around Rio de Janeiro—77,000 were displaced to make way for the Olympics.

But what sticks with me is each one of those 77,000 people has their own story. And when I went back and visited Vila Autódromo with a resident who I’d come to know, her name is Heloisa Helena Costa Berto.

When I visited Vila Autódromo with her, we stood behind a chain link fence and we looked through it at where her house used to sit.

And she was just crestfallen. She was heartbroken because basically they smashed down her home to make way for a parking lot outside the media centre.

And she’s a practitioner of the Candomblé religion. And her orixá or her god, goddess, was located right along the water there of the Jacarepaguá lagoon where her house sat.

So it wasn’t just like getting her to move to another part of the city was gonna be just fine, even if it was a nicer apartment. And my understanding is it wasn’t. But she lost part of her spiritual core having to move away from the Jacarepaguá lagoon.

And, you know, one time I was walking around with her and I, she invited me to a, the ceremony when she was letting go of her, of her home. It was beautiful. I was just honoured to be there.

And walking through the, walking through Vila Autódromo that day and just reflecting on it, I was just by myself. I just needed to decompress. ’Cause this is, for me, very real and very intense, and it’s kind of stories you’re not gonna really hear often.

But I remember walking around that day and I picked up a few pieces of, like clay from the, the houses that were bashed down.

ANDIE

Oh. You carry it with you.

JULES

I carry it with me. When I go to a new Olympic city, I always try to keep it in my pocket to remember like, “Why do I do this stuff?”

And certainly not to amplify me around the world. It’s to try to like, figure out ways of better understanding how these events actually affect real people. And that’s why I do it.

ANDIE

Oh wow.

JULES

I mean, I don’t do it to—god bless you, Andie. I don’t do it to show up on a podcast with you as much as I enjoy walking around Paris with you right now.

ANDIE

[laughs]

JULES

But the reason why I do it is because I deeply believe in justice. I deeply believe in the injustices around the Olympics need to be rectified for people like Heloisa Helena Costa Berto, and for thousands and thousands of others whose names we probably will never know.

Yeah. Pull out the, the little like piece of clay for a podcast when you can’t even see it.

ANDIE

No, honestly, I’m, I’m kind of, you have me at a loss for words. It’s uh, with the people that you met in Rio, the people that you met in London, the people you met in Vancouver.

These are individuals, these are their lives, these were their homes, and they are not statistics.

JULES

Well, it’s just a thousand people in London. That’s nothing. Those are a thousand people whose lives got—their communities were shattered. This was their existence, and they didn’t really get proper recompense for that.

I don’t know if you can, really can provide proper recompense for shattering a community.

ANDIE

Do you see any evolution, any change, any improvement knowing that you’ve, since you’ve been following the game, since the, uh, Vancouver games in 2010, are, are we getting any better at this?

Are we getting any better at hosting these kinds of mega events in ways that are, that are more inclusive, that are, uh, less damaging to vulnerable communities, to people who are unhoused or who struggle with housing?

JULES

Well, I think that each Olympics is different and sort of needs to be treated as such.

But there are certain patterns. And one of those patterns is the people who organise the Olympics say that they’re going to help with housing.

So whether it was Vancouver having a huge social housing component, whether it was the London Olympic Village that was built that was also supposed to have for working class people, apartments, neither of those worked out for those.

So, you know, you have to approach every situation with a certain amount of healthy skepticism just based on the histories.

I think with Paris, I guess you could say that they’ve dialed back some of their promises. They don’t have those grand promises. I mean, they’re still promising some social housing as part of what we’re expected to see with the Olympic Village.

But I’ll believe that when I see it just based on history with the Olympic Villages of the past. So, no, I think if anything, what you’ve seen is in terms of evolution around the Olympics is the messaging and the PR machine around the International Olympic Committee has only become more refined.

They understand what the arguments against the Olympics and the downsides that people who have been lofting into the discourse are. And they’ve come up with ways of dodging the reality instead of trying to change the reality.

I think that they have a certain responsibility. I mean, they tell everybody that the Olympics are gonna be a big deal when they come to your city, and they’re right.

With that responsibility, I think, comes a certain amount of necessity for action.

HOST

Looking ahead at the coming weeks, there’s a lot on the line here for Paris—because France is doing this all again in six years. It’s hosting the 2030 Games in the French Alps.

And there’s also a lot on the line for the IOC. The promises of a better Olympics—where the games adapt to the city and not the other way around—Jules Boykoff is not optimistic.

JULES

They’ve just always really tightly circumscribed what they view as their remit, what they view as their responsibility.

And I think if the Olympics really wanted to change for the better and directly address a lot of the critiques that city after city has been making against them, they would start to rethink that limited remit and stop circumscribing it so tightly.

And instead thinking, what can we actually do to make a positive difference in a society since it is a big deal and they’re going way out of their way, and they’re spending billions of dollars to host us here, what can we do in return?

Except they’ll tell you, “Oh, we bring the best athletes in the world.” And that’s, that’s true, but it’s time to move well beyond that.

ANDIE

Jules, it’s been an amazing day getting lost in Paris with you. Thank you.

JULES

Thank you. It’s a lot of fun. Now, where the hell are we?

ANDIE

I don’t know! [laughs]

HOST

Coming up on the next episode of State of Play, we’ll travel to my hometown, Vancouver, and we’ll find out more about what happened there in 2010…

The promises made and broken when the Olympic circus moved on.

GREGOR ROBERTSON

We had a skyrocketing crisis, you know, for almost a decade before the Olympics. That’s one of the reasons why I got into politics.

The Olympics lit that match in Vancouver. And we haven’t been able to keep up on the construction and affordability since then.

HOST

State of Play is brought to you by the Global Reporting Centre and PRX.

Hosted by me, Andie Crossan.

Produced by Sharon Nadeem and Katarina Sabados.

Our senior producers are Sarah Berman and Jesse Winter.

Audio post-production by Newfruit Media with sound editing and mixing by Aaron Keene and Daniel Rinaldi.

Digital production by Andrew Munroe.

Archive by Bea Lehmann.

Fact checking by Juliana Konrad.

Art by Will Brown.

Our executive producer is Britney Dennison.

Special thanks to the Global Reporting Program at the University of British Columbia.

–END–