Listen now

Episode transcript

HOST (ANDIE CROSSAN)

And that’s a wrap.

The Paris Games of 2024 are officially closed.

But we’re left with the memories. Like Celine Dion singing, Simone Biles soaring, and Snoop Dogg carrying the Olympic torch.

Throughout this podcast, we’ve been meeting the people whose lives have been forever changed because their city hosted the games.

People in Vancouver, Los Angeles, and of course Paris.

In our final episode of the season though, we wanted to look at the Games from different perspectives.

Through the eyes of a fan, an athlete — and the folks that run the show, the International Olympic Committee.

And we ask the question: Is there a way to host the games where fans can cheer, athletes can compete, and all the residents in a host city can benefit? In other words, how do we win?

This is State of Play. I’m Andie Crossan.

One thing I haven’t talked about in this podcast is my little secret. Here it is. I love sports.

I mean — LOVE sports.

Whether it’s Vancouver Canucks hockey, Boston Red Sox baseball, or US college football.

I’m in.

And I love watching the Olympics.

I even made the journey to London in 2012 to go to the Summer Olympics there.

So when I embarked on this journey to meet the people impacted by the games, I wanted to visit with someone who had very different memories of that time. So let’s go back in time…

In the summer of 2012, London was buzzing.

Union Jack flags were hanging in store windows and Brits were sporting their traditional summer attire — plastic rain ponchos…

And as the games got closer, there were whispers of an Olympic-sized event that the world had been waiting for…

REPORTER

Is it right that you guys might be reforming for the opening ceremony of uh, you know the Olympics in 2012? We’ve heard a rumour.

EMMA BUNTON (BABY SPICE)

These are, these are rumours that I’ve been hearing, obviously how amazing would that be? I–I would love it personally, but um, it’s just a rumour.

HOST

That’s Emma Bunton — also known as Baby Spice on British TV.

And that summer, we got what we really, really wanted.

The Spice Girls reunited, riding around on top of black cabs at Olympic Stadium.

And here was another epic moment of the games.

That’s the sound of then-mayor Boris Johnson ziplining across a park while waving little flags.

BORIS JOHNSON

…a good idea. Can you get me a rope? Get me a rope, okay?

HOST

It’s actually the mayor stuck on a zipline. Johnson dangled there for a good ten minutes before he was winched down.

The stunt was a rare gaffe during a summer where the Olympics were celebrated by many as a roaring success.

And like all Games, there were promises made.

Specifically around the transformation of a low-income area of East London.

Here’s the head of London’s Olympic Organizing Committee, Lord Sebastian Coe, reminiscing about his vision for the community.

LORD SEBASTIAN COE

And I remember standing there saying sort of, well, you see where that rotting pile of fridges is over there well that’s where the stadium’s going…

HOST

Sebastian Coe won medals in track and field in the 1980s, and is a major influence in the international sporting world today.

SEBASTIAN

And all that, well that’s going to be 3,000 affordable houses for Londoners in the area. And I guess, you know, for me the essence of that journey was, that day where, you know, we showed what the vision was, but there was nothing there to show.

JULIAN CHEYNE

I actually moved to Stratford before in 1987. I came to live with some friends, then I moved out again and came back to live at Clay’s Lane. So I was, I’ve been here more or less constantly since 1987.

ANDIE CROSSAN

Don’t, don’t, don’t get me killed. But [laughs]… walking across traffic.

HOST

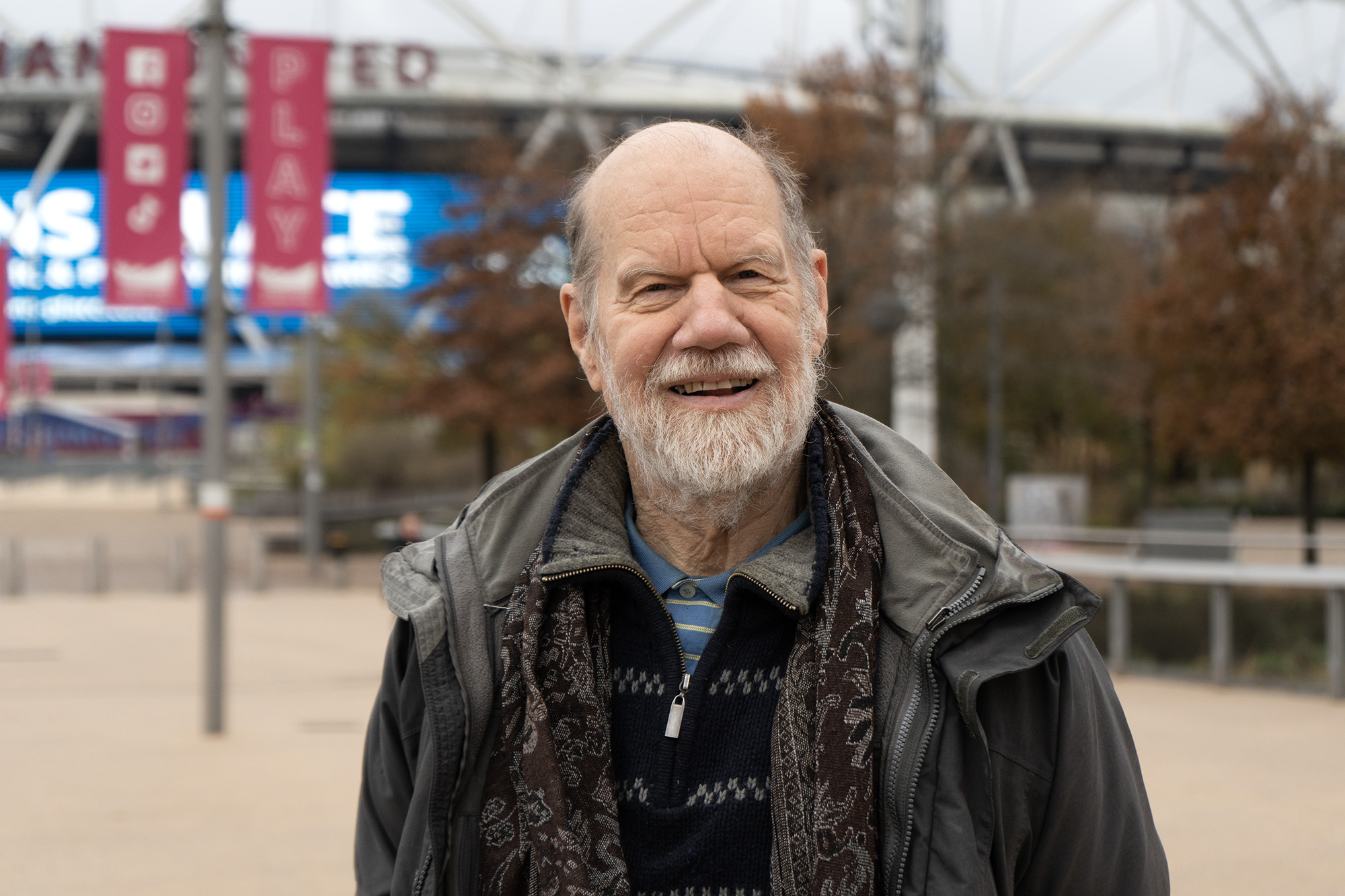

This Is Julian Cheyne.

He’s the person I’ve traveled to London to meet.

For a man over seventy, he’s a fast walker.

JULIAN

British people. I dunno if you notice, they walk all over the roads, all over the place. So…

ANDIE

Well just remember, uh, I’m, I’m a good Canadian who’s looking the wrong direction for cars.

JULIAN

That is also true, but I’m watching out for you, don’t worry.

ANDIE

Okay, thank you [laughs].

HOST

Drivers outside of East London’s Stratford tube station are not slowing as we scramble across the road on our way to Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.

This was the epicentre of the London Games — where venues like the Olympic Stadium, the swimming pool, athlete’s village, and media centre were built.

But before all that, there was a place called Clay’s Lane.

JULIAN

Right. Well, where I used to live is straight ahead. It’s that block. You see that?

ANDIE

So the building that’s like a, the, the five story block that’s right in front of us?

JULIAN

Yeah, yeah. It’s just behind that. So the athlete’s village is the one on the right.

HOST

A home where he lived for 16 years.

JULIAN

I don’t romanticize Clay’s Lane — Clay’s Lane had its good points. It had the beautiful green open space next door, um, which I used to go and, uh, sit on and look at the, uh, heron. Although, at times I was so ill that I couldn’t actually walk onto the green space. At times I was housebound, virtually.

HOST

Julian has struggled with significant health issues for most of his life. He has myalgic encephalomyelitis — also known as chronic fatigue syndrome.

JULIAN

I couldn’t work at all. I mean, I was completely knackered, absolutely exhausted. I mean really I was housebound. At one point I couldn’t read a newspaper.

The only thing I could do was look at the TV, quite literally. That’s all I could do. If I read a newspaper, I got exhausted. By the time I read the front page, I was exhausted.

HOST

Clay’s Lane was specifically built as housing for vulnerable single people like him.

It was a series of shared houses and individual bungalows with communal courtyards.

The two- and three-story red brick buildings were clustered together next to a peaceful marshy area near the River Lea.

And despite the odd disagreements, according to Julian, the co-op was a nice place to live.

But everything changed in the winter of 2003.

Even before London won the bid for the games, representatives from the London Development Agency came to Clay’s Lane to present the plans.

JULIAN

I mean, basically the whole thing happened very quickly. Uh, they came to speak to us in Clay’s Lane and they, uh, they had three diagrams and they said, this is what’s gonna happen with the Olympics. How wonderful. An hour of telling us how wonderful it was.

HOST

And when London won the bid for the Olympic Games in 2005, the deal was done.

Julian remembers when he heard the news.

JULIAN

Well, I was devastated. I mean, devastated myself, ’cause I knew I was gonna get kicked outta my home.

HOST

Julian was one of around 450 residents issued with orders to leave Clay’s Lane.

Residents received some compensation and help finding accommodation.

In the summer of 2007 when the evictions began, Julian was moved into temporary housing.

Now, his little bungalow next to the park is gone and has been replaced by a multi-story condo complex — and the neighborhood’s now called East Village.

It’s the poster child for urban regeneration.

Where East London has overcrowding and deprivation — with high rates of poverty and unemployment. East Village is like a bubble of affluence — the population is younger, whiter and wealthier than the neighborhoods that surround it.

One bedroom apartments here rent for around 2500 hundred pounds a month. That’s around 3200 US dollars.

JULIAN

I know there are a lot of people living in East Village, they really like living here. I mean, they are living next door to a nice open space.

So I can’t say, oh, you know, nothing has come of this. But it’s not what they said it was going to be. And it hasn’t contributed what they claimed it was gonna be.

HOST

The grand plan for the post-Olympic area was large-scale regeneration and investment in what was historically the poorest part of London.

And there were big promises made for social housing units to be built as part of the project.

At this point it won’t surprise you to learn that there was a financial crunch, a government bailout, and deal with a developer that shaved away much of the social housing.

Earlier I shared that I went to London in 2012 as an Olympic fan.

I went to see boxers duke it out in an Olympic ring near where I’m walking with Julian.

I remember having a blast that night. I went there alone but managed to ingratiate myself with a group of fans from Kazakhstan.

They gave me a pair of turquoise and yellow plastic tubes called thunder sticks, which we would whack together to create a racket every time a Kazakh boxer landed a punch.

And to be honest, I never thought about the residents — people like Julian — who were pushed out of their homes so that I could cheer on amateur boxers.

ANDIE

I guess, this is, this is a tough question, but—

JULIAN

Yeah.

ANDIE

When the Games happened, was there any part of you, was there anything that you saw and thought that there was value in it?

JULIAN

No, absolutely nothing. Sorry, I really have to say that. I didn’t see any of the Olympics. I didn’t watch it.

No, hand on heart, I can say the whole project was complete nonsense and I had absolutely no interest in it.

And that actually, it’s really turned me off sport. I’m really quite hostile to sport now because I think sport is very bogus. It’s full of loads of claims about benefits, which are just not realized.

HOST

Walking around London’s East Village with Julian Cheyne, reminded me of a place much closer to home.

Vancouver.

The story of Vancouver’s athlete’s village is all too similar to London’s. Promises made that most of the apartments would be allocated for social housing, a development company that didn’t have the money to complete the project, the city taking over the costs and most of the units being sold at market rate.

It’s in the former athlete’s village where I meet Christine Nesbitt.

[Sounds of skates on ice]

She’s a three-time Olympian.

A gold medal-winning speedskater for Team Canada.

ANDIE

Well, I will start off by saying you are the first Olympic gold medal-winning athlete I’ve ever met, so I’m feeling a little starstruck this morning.

CHRISTINE NESBITT

Oh, don’t, don’t feel starstruck. It feels like a lifetime ago, so.

HOST

Christine lived here in 2010 during Vancouver’s Olympic Games.

And as cool as it is to meet an Olympian, I’m here to talk to Christine about the chapter of her life after she hung up her skates.

After she retired, she studied urban planning at the University of British Columbia.

CHRISTINE

I wrote a thesis that was really focused on Olympic village legacies, particularly housing, how they impact a city’s housing market. I zeroed in specifically on affordable and social housing.

HOST

She explains that participating in the Games as an athlete gave her a front row seat to the ways that the Olympics impact people in the host cities.

CHRISTINE

It has been well documented in every recent Games of people who are unhoused being quote unquote swept off the streets during the game so that it looks nice for tourists, just displaced for no regard for the community that they have.

It’s just ridiculous, kind of, like, it’s like you’re only as good as how you treat the people who are the most disadvantaged. So you’re getting all this influx of funding and you want this jewel in your crown, so to speak.

Um, but if you’re not uplifting those who need it most, then it’s just, it’s, it’s just perpetuating the same cycle.

HOST

I asked Christine how cities could avoid falling into the trap of overpromising and underdelivering on those Olympic legacy commitments.

CHRISTINE

In a perfect world, you already know all the things that your city needs, all of the big ticket items that you want to leverage, what funding that the games unlocks to deliver on these things.

Which I think is the upside of the Games because we’ve had so many austerity measures for decades now, and we have seen that across the globe, and we’ve seen a lot of community amenities and programs, um, be underfunded for decades.

That is the opportunity that the Games bring.

HOST

Opportunities like improving public transportation and building roads and highways.

Those were the kind of major investments that were made here in Vancouver.

But as we’ve heard over and over again in the making of this series, the Olympics have become a tough sell.

CHRISTINE

I mean it’s quite visible these days, the dark underbelly of hosting the games and of the IOC.

That’s a huge part of why you’re seeing fewer cities vie for the games. It’s like every city that’s hosted the games has overshot their budget by, in some cases, like hundreds of percents, 700%…

HOST

So this is an opportunity according to Christine.

CHRISTINE

…the IOC I think has been in a position for a long time where it just dictates, right? It’s not flexible. They’re not flexible. They’re, it’s setting out essentially a list of demands that must be met.

Um there’s so much discontent around the Games and with the IOC that they’re actually, this is a time where cities and host countries can actually make new proposals and push back.

The IOC is not, doesn’t have its strength, that it has had in the past.

HOST

I promised at the beginning of this episode that you would hear from a fan, an athlete, and from the IOC.

I called up Tania Braga, the head of Impact and Legacy with the International Olympic Committee.

ANDIE

Uh, thanks so much for making time to speak with me today, Tania.

TANIA BRAGA

Thank you, Andrea. Nice to meet you.

ANDIE

It’s really nice to meet you. So when it comes to legacy and impact, how does the, how do you, within the IOC gauge success?

TANIA

Success is measure, measured by whether the Games is useful for the city. And what do we mean by that?

Our objective is that the Games adapt to the hosts, the host city, the host region, and not the other way ’round.

The idea behind that is that the Games would help to accelerate the development plans of the, the host city or the host region and create the momentum for, uh, lasting socioeconomic benefits for the local communities.

ANDIE

Is it fair to say that that’s kind of a sea change within the IOC in terms of adapting to the city as opposed to the city adapting to the Games?

TANIA

Yes. This change has been at the heart of the agenda, Olympic Agenda 2020, where, uh the IOC, uh make transformations for how the Games is conceived and delivered. So the point was to create more flexibility and to add more value for the host cities and regions.

Before we start in this process of dialogue with interested parties for future Games, the first thing we ask is why do you want to host the Games?

How hosting the Games will help you to develop the city in the direction that has been agreed with the local stakeholders.

ANDIE

That’s a really good point because when we get into stakeholders, I think a lot of the folks that we’ve been speaking to throughout the making of State of Play are stakeholders in communities in Vancouver, in Paris, in Los Angeles.

And there are questions around the, the ways that still, the urban transformation of these cities, there are impacts that are negative to those who quite often are vulnerable communities, unhoused people.

There is a significant amount of criticism from activists around gentrification and how unhoused people are still pushed out of host cities. Does this give you pause? Are you concerned?

TANIA

Of course, we, we concerned with the wellbeing of people, and this is a big part of the conversations we have with the hosts before electing.

The IOC has recently also, uh, adopted a strategy on human rights and making sure that hosting the Games cause no harm.

It’s a principle. And as part of the changes we did, for example, we now encourage the interested parties in hosting the Games to use, um, existing venues or temporary ones.

ANDIE

And I think that there’s a conversation around the idea of a no build Olympics. The idea that, again, as you were talking about using existing buildings as opposed to constructing big new stadiums.

One activist I spoke to talked about how it would be great if the promise was not no build as opposed to no displacement. Do you see a possibility or a future where a Games could come to a city and there would be no displacement of people?

TANIA

Uh, no displacement is already part of our human rights policy, and this is considered before we start talking with, uh, to elect a host, we make sure that there is no displacement directly related to the Games and that there is nothing built on conservation or cultural heritage.

So these are already principles. Of course, we cannot be responsible to say that there will be no displacement in the city or the region that are related to other projects.

The important thing to understand here is that sometimes even if you have zero construction, the city development that’s not related to the Games can have some displacement and people sometimes, I would say there is lack of clarity on what is related to the Games or not.

So a big part of the criticism around displacement are indeed related to projects that are not related to the Games.

ANDIE

In this episode we’re looking at the future, what the Olympics can look like in the years to come and knowing that there have been a number of cities in previous years who have withdrawn their bid to host the games. What’s your elevator pitch for cities that are considering hosting? Why do it?

TANIA

I think the first point is to know why you want to host the Games. They need to know that the vision they have for their territory is a good match.

So it has to have a clear direction. The second point is to make sure that there is a conversation with local stakeholders that this is a collective project and not an isolated project.

ANDIE

Tania Braga, IOC’s head of Olympic Games Impact and Legacy. Thank you so much for your time.

TANIA

You’re welcome.

HOST

So that’s the view from the IOC.

That it’s more flexible — and that the intention is to have the Olympics adapt to the city and not the other way around.

But the reality can look very different — for people evicted from squats in Paris to people in LA being moved out to make way for hotels — the Games leave a lasting mark on their lives and their communities.

So for people like me who really like watching the incredible human achievement like what we’ve witnessed this summer in Paris — what can we do to reconcile our love of the Games and the problematic things that they bring?

I put that question to our go-to expert, Jules Boykoff from Pacific University in Oregon.

As a former professional soccer player who’s authored six books about anti-Olympic activism and protest movements, I know that this is something he’s thought a lot about.

JULES BOYKOFF

I think you can be a fan of Olympic athletes without necessarily being a fan of the Olympics in total.

There’s no questions that the sports world today, the, the hyper capitalist sports world of today, brings all the problems of hyper capitalism to it.

And so there’s no surprise to me that sports in the modern era are filled with justice issues and justice problems. And so I think actually those who care about sports in some ways are best positioned to fight back against the injustices that are all too often bricked into sport.

It’s one of those things that if you care about sports and you truly care about sports and the wellbeing of athletes, it seems like it’s a great opportunity for you to slow down, learn more about the wider structures that are informing those athletes that you love, and maybe to try to stand up with them, and for them, for them to get a better deal out of the sports that they’re dedicating their lives to.

HOST

Jules also argues that we need to give power to the people.

JULES

A no brainer for me, is to have a public referendum for every single Olympic bid.

If you want to bid on the Olympics, not only do you have to write a feasibility study, which they all do, but they also have to fund a referendum so that everyday people in the potential Olympic city have a chance to weigh in…

Some people have suggested that maybe putting the Olympics in one place and just keeping it there would be a wise way to move forward, or maybe putting it in different cities and rotating it among a small group of cities.

That could be interesting. It would certainly limit the costs involved in hosting the Olympics. The only problem with that is the International Olympic Committee has expressed zero interest in either one of those options.

HOST

So as Jules points out, the ideas for how we win seem to always come down to one major obstacle. The IOC.

JULES

I’ve never met a single person who has said, I watched the Olympics because I want to watch the guy who’s a member of the International Olympic Committee sit in the seventh row and make $900 a day because he’s on the executive board and per diem.

They watch it because of the athletes and there’s athletes across the world that think that they deserve a fair shake. And I happen to agree with them on that issue. And I think they do.

If the International Olympic Committee is not allowed to do that, then I think the International Olympic Committee needs to go.

So what I’m suggesting to you right now, is that if they’re not willing to improve democratic practices outside of the Olympics and inside of their organization, if they’re not willing to take athlete concern seriously about payment and also abuse, it’s time for the International Olympic Committee to go.

HOST

Because in the end, it’s the athletes’ achievements that we as fans want to celebrate.

More than ever, the world is watching.

The Olympic cauldron in Paris is extinguished.

The torch passed on.

And the Olympic circus will move on.

Thanks for listening.

State of Play is brought to you by the Global Reporting Centre and PRX.

Hosted by me, Andie Crossan.

Produced by Sharon Nadeem and Katarina Sabados.

Our senior producers are Sarah Berman and Jesse Winter.

Audio post production by New Fruit Media, with sound editing and mixing by Daniel Murcia and Daniel Rinaldi.

Digital Production by Andrew Munroe.

Archive by Bea Lehmann.

Fact checking by Juliana Konrad.

Art by Will Brown.

Our executive producer is Britney Dennison.

Special thanks to the Global Reporting Program at the University of British Columbia.

–END–